by Polydamas

Several days ago, a Turkish columnist by the name of Yuksel Aytug wrote in the daily newspaper Sabah a column titled “Womanhood is Dying at the Olympics” (http://bit.ly/N55J4f). In his column, Aytug wrote that the Olympic Games were “distorting” the female figure. According to the Hurriyet Daily News, Aytug said that female athletes are “broad-shouldered, flat-chested women with small hips” who are “totally indistinguishable from men.” He continued, “their breasts – the symbol of womanhood, motherhood – flattened into stubs as they were seen as mere hindrances to speed.” He decried the appearance of female Olympians as “pathetic” and made sure he was understood that he was “not even talking about female javelin throwers, shot-put athletes, weightlifters, wrestlers and boxers.”

Needless to say, Aytug’s harsh commentary on the aesthetics of the female athletes was met with severe criticism of sexism and “lookism”. Some of Aytug’s critics decried that he was discriminating against women on the basis of their gender and, if men can have muscles, so can women. Another group of critics savaged him for his shallowness, and that a man had no right to judge women at all, much less on their body parts.

To be certain, Yuksel Aytug is completely incorrect in his aesthetic assessment. However, his many critics are not, altogether, correct in their objections either. Aytug’s personal opinion is clearly wrong, but not for the reasons that his detractors point out.

To preface the discussion here, it must be noted that we at The Cassandra Times are somewhat biased. We, like the ancient Greeks, are a contemplative, philosophical bunch, and we view the Olympic Games as an ode to the human body and its excellence. We also admire, purely aesthetically, the sleek, muscular bodies of the Olympic athletes, both males and females, and laud the hard work and dedication that they invested in their bodies and crafts. Thus, Aytug’s aesthetic judgment is immediately suspect in our eyes.

The defense of the aesthetic appeal of the female Olympians, nevertheless, cannot rest solely upon our subjective notions. If beauty is truly in the eye of the beholder, then our subjective ideas of what a beautiful female body is will be no better and no worse than Aytug’s subjective notions of female beauty. There must be, therefore, an objective reason to prefer our vision over his.

Our objective defense of the female Olympians’ bodies begins thousands of years ago in the ancient societies of the world. Going back to antiquity, the hunter-gatherer paleolithic society ate an omnivorous diet of game animals with thick layers of subcutaneous fats, including their organ meats, and supplemented them with fruits, berries, nuts, roots, and leaves. According to the superb Weston A. Price Foundation‘s article “Caveman Cuisine” by Sally Fallon Morell and Mary Enig, “a large portion of the primitive woman’s day was spent in just such preparations-pounding, soaking, sieving, souring and putting the finishing touches on various types of root and seed foods. The men, on the other hand, divided their time between dangerous hunting forays, in which physical stamina and strength was at a premium, and periods of idleness when they would work on their weapons”. (http://bit.ly/wUE3nz).

Our ancestors labored during the day and ate at night around the fire. There were always periods of feast or famine, the latter taking place when the hunts were less successful and when game animals were less plentiful. In times of famine, our ancestors survived by breaking down their own subcutaneous fat. Because of the general scarcity of food, prehistoric men and women were far leaner than we are. During more plentiful times for the tribe, the women’s body fat level increased sufficiently to allow them to become pregnant. After a successful pregnancy and delivery, with increased physical activity and scarcity of food, their bodies eventually returned to their previous level of leanness.

All of the hard physical labor that our ancestors did on a daily basis produced men and women with hard, sinewy muscles. They did not live the sedentary lives of modern men and women. They did not eat the variety of carbohydrate-rich breads, pastries, and sweets that afflict the modern diet. Food in the paleolithic or the neolithic eras was never so plentiful as to result in sustained overconsumption. The rigorous daily rituals of survival, hunting for food and shelter required constant physical exercise and the expenditure of energy that overweight and obese individuals were quite impossible.

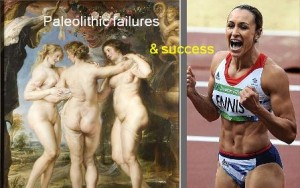

The female Olympians of today and modern athletic training methods have, wittingly or unwittingly, duplicated the dietary and physical conditioning elements of the paleolithic and neolithic eras. The female athletes eat carefully controlled diets and largely eschew the modern carbohydrate-rich breads and sweets in favor of a diet that feature animal proteins and vegetables. The female athletes voluntarily abstain from the same foods that were completely unknown and unavailable to their female ancestors. The athletes’ physical level of fitness is accomplished through hard work that emphasizes strength, explosive power, and endurance, achieving purposefully the level of fitness that paleolithic women needed to have just to survive.

If we had a time machine and could travel back in time, we could send a female Olympian of today to the paleolithic era and, even though she would have to learn the specific survival skills of the era, she would fit in with the other women in terms of physical strength, power, and endurance. Conversely, a cave woman could be brought to our times and, if taught the skills of a particular sport, she would be a formidable competitor.

The aesthetic tastes of Yuksel Aytug for plump and curvy women, the so-called “Rubenesque” women, are a relatively new phenomenon, compared to the many thousands of years beforehand. Peter Paul Rubens’s famous paintings of the 1600s, “The Three Graces”, “Women”, “Venus at the Mirror”, depict soft, indolent, and overweight aristocratic women who could not last even a single day in prehistoric times. Rubens’s paintings of plump and curvy women were only representative of the small circle of aristocratic and noble born women with whom Rubens interacted socially or whom he used as his life models or whose wealthy parents and husbands commissioned him to paint. These women of social and economic privilege ate carbohydrate-laden delicacies, did not deign to exert themselves overmuch physically, and could not climb two flights of stairs without fainting from the exertion. In contrast, the vast majority of women of the 17th century or the centuries beforehand, who were not of aristocratic backgrounds or lived lives of privilege, had to live a more spartan existence and worked hard physically to maintain their families and homes. Their lives were marked by austerity and physical labor. They did not consume a significant excess of calories over their base caloric maintenance requirements to become plump or curvaceous.

This is not to say that the wealthy, aristocratic men of the 17th century were in any way the paragons of physical fitness. When artists painted and sculpted their wealthy male patrons, their subjects were equally as plump and overweight as the women due to the same unhealthy food selections and lack of physical exercise. There are no paintings by Peter Paul Rubens and other contemporary or later artists that depict naked, adult aristocratic men since such paintings would not have been considered in that era to possess any aesthetic merit. However, to the discerning eye, even clothed, the proportions of rotund, aristocratic men also fall far short of Leonardo Da Vinci’s painting of “Vitruvian Man”, Michelangelo’s sculpture of “David”, the ancient Greek sculture of “Laocoön and His Sons”, and other classical works of art whose muscular proportions and washboard abdominals are much closer to the achievable ideals of male beauty.

The degeneration in physical fitness that had been restricted to the wealthy few in previous centuries spread throughout the population of the industrialized world in the 20th century. For example, in the Southern United States of the 18th and 19th centuries, obesity was an isolated phenomenon that was confined to wealthy southern gentlemen who waddled on their gout-inflamed feet with the aid of their canes and their equally obese families. Now, according to the Center for Disease Control’s 2010 statistics, obesity afflicts 32.2% of Alabamans, 30.1% of Arkansans, 26.6% of Floridians, 29.6% of Georgians, 31.3% of Kentuckians, 31.0 of Louisianans, 34% of Mississippians, 30.5% of Missourians, 27.8% of North Carolinians, 30.4% of Oklahomans, 31.5% of South Carolinians, 30.8% of Tennesseans, 31.0% of Texans, 26.0% of Virginians, and 32.5% of West Virginians. (http://1.usa.gov/nUm8Zf). Obesity, heart disease, diabetes, and gout, formerly known as the disease of the wealthy few, spread throughout the civilized world during the 20th century because of labor-saving machinery that promoted a sedentary lifestyle as well as the easy availability of cheap, mass-produced, and unhealthy carbohydrate-laden foods.

In truth, the aesthetic standards of Yuksel Aytug and of other like-minded 21st century men and women who decry the Olympian females’ appearance have become debased over time. Their eyes have become so habituated to seeing the unhealthy proportions of the overweight and obese women around them that they became their aesthetic standard of what is considered normal. The men and women who assail the muscular proportions of the Olympian females do so in order to justify to themselves their own sedentary lifestyle choices and unhealthy food selections. It is far easier for them to criticize the supposedly masculine bodies of the female Olympians as freakish than to adjust their own faulty aesthetic standards, exercise in earnest, and resist yet another tub of ice cream and a pizza pie the size of a satellite dish.

Far from destroying womanhood, the Olympics and the pursuit of excellence allow women to rediscover and to reclaim their innate, hardy natures. One is, thus, reminded of the famous words of legendary, trailblazing architect Louis Henry Sullivan and originator of skyscrapers:

“It is the pervading law of all things organic and inorganic,

Of all things physical and metaphysical,

Of all things human and all things super-human,

Of all true manifestations of the head,

Of the heart, of the soul,

That the life is recognizable in its expression,

That form ever follows function. This is the law.”