The Road to Ruin or to Salvation—by Polydamas

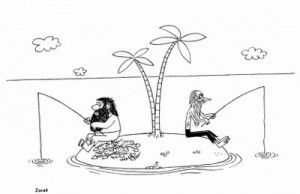

There is an apocryphal, yet, nonetheless, amusing story about a chemist, an engineer, and an economist who were shipwrecked on a barren desert island. They had with them a large supply of canned foods, but, unfortunately, they lacked a can opener. While the chemist and the engineer engaged in a lively conversation on how they may use their knowledge of chemistry and engineering to extract the food from the cans without the aid of a can opener, they were interrupted by the economist. “Let us assume,” he said to them, “that we can open the cans. We need to decide how we will divide them among us.”

With this story in mind, let us consider the recent, breathless reporting in the national media about a company called Planetary Resources, Inc. This company, launched at the Museum of Flight in Seattle, Washington on April 24, 2012, plans to prospect for and extract precious metals from near-Earth asteroids. The investors in this, literally, out-of-this-world business venture are far from being the adoring science fiction fans that frequent conventions in imaginative garb and engage in lively debates about whether the Star Wars universe is superior to that of Star Trek or vice versa. Rather, the list of investors reads like the Terra firma of the high tech world, Peter Diamandis, Eric Anderson, Google’s billionaire founder Larry Page, Eric Schmidt, Microsoft’s Charles Simonyi, Ross Perot Jr., and even renowned Hollywood Director James Cameron of Terminator, Titanic, and Avatar fame.

The average earth-bound citizen may wonder why would such an august collection of financial luminaries chose to invest their time and substantial monies in such a seemingly pie-in-the-sky venture. At Planetary Resources’ inauguration, co-founder Peter Diamandis explained, “since my early teenage years, I’ve wanted to be an asteroid miner. I always viewed it as a glamorous vision of where we could go.”An April 26, 2012 article by Chris Taylor titled “This $20 Trillion Rock Could Turn a Startup Into Earth’s Richest Company,” (http://mashable.com/2012/04/26/planetary-resources-asteroid-mining-trillions/), offers a far more practical reason – a new gold rush offering stupendous riches awaits intrepid adventurers. According to University of Arizona planetary sciences Professor John S. Lewis and author of Mining the Sky: Untold Riches from the Asteroids, Comets, and Planets, a small, mile-wide, metal-bearing asteroid named Amun 3554 could yield $8 trillion worth of platinum at $1,500 per ounce, $8 trillion worth of iron and nickel, and $6 trillion of cobalt. Amun 3554 is expected to be only one of a multitude of such M-Class near-Earth asteroids which could be mined at a tidy profit by Planetary Resources and other companies like it. Even Peter Diamandis proclaimed at a space development conference in 2006 that “There are $20 trillion checks up there waiting to be cashed”.

Leave it, however, to the professional and amateur economists to douse Planetary Resources’ monumental dream in ice-cold water. In The Economist article of April 28, 2012, titled “ Going Platinum,” (http://www.economist.com/node/21553419/) the dyspeptic, yet self-important argument was made that:

“the real doubt over this sort of enterprise is not the supply, but the demand. Platinum, iridium and the rest are expensive precisely because they are rare. Make them common, by digging them out of the heart of a shattered planet, and they will become cheap. The most important members of the team, then, may not be the entrepreneurs and venture capitalists who put up the drive and the money, nor the engineers who build the hardware that makes it all possible, but the economists who try to work out the effect on the price of platinum when a mountain of the stuff arrives from outer space.”

The presumption of The Economist to elevate economists, the would-be allocators of prosperity above the actual producers of prosperity is reminiscent of the earlier story about the chemist, engineer, and economist stranded on the desert island. If a brilliant scientist discovered a medicine that cured cancer, it would seem that The Economist would hold in higher esteem the economists whose job was to work out the effect on the price of the medicine when a mountain of the plentiful medicine was distributed to those afflicted with cancer. Perhaps The Economist would consider the real heroes to be the economists who calculated the incremental drain on the economy effected by people who no longer died of cancer, but lived out their normal life spans.

In stark contrast to The Economist’s flippantly superficial take, Jeff Taylor’s April 27, 2012 article in The Economic Voice, titled “The Economics of Asteroid Mining” (http://www.economicvoice.com/the-economics-of-asteroid-mining/50029414#axzz1uGIsCW3e), made a number of cogent points. He correctly noted that these metals have a more inherent value, based upon their usefulness in the medical and electrical industries, that is separate and apart from their market value as scarce commodities. He also intelligently suggested that Planetary Resources and similar companies would not simply dump a mountain’s worth of precious metals from mined asteroids on the terrestrial market, but would, instead, carefully control the supplies to maintain scarcity and high commodity value in much the same way as the De Beers cartel does for diamonds.

Jeff Taylor also predicted substantial involvement by governments. “Apologies for the cynicism but the likely outcome would be that licenses would be needed, huge taxes levied and quotas set to ensure that the markets were not damaged. Vested interests and lobby groups would fight to maintain the value of these metals. We can’t have any old Tom, Dick or Harry flying off into space and bringing back a few pounds of precious metal can we?”

Mr. Taylor raises an interesting point here. What, indeed, should be the proper role of terrestrial governments in the mining of asteroids outside of Earth’s orbit? On what basis should governments license, heavily tax, and stringently regulate these private ventures which do not use government tax money as their source of capital? Government did not contribute to the infrastructure and pave the roads, so to speak, that benefit Planetary Resources, Inc. because there is no infrastructure and there are no roads in space. Let us backtrack for a moment and come back. In the olden days, the analysis was far simpler. Christopher Columbus discovered the New World and promptly claimed vast portions of it for King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella of Spain. The Portuguese, French, and British monarchs also had their respective explorers stake out lands on their behalf and assert crown ownership over them. Setting aside, for the moment, any prior ownership rights that the indigenous people may have had over their lands, no one questioned the kings’ right to claim distant, previously-unclaimed lands as their own as their moral and legal authority was believed to have originated from God. Also, the explorers’ claiming the newly-discovered lands on behalf of the respective monarchs of Spain, Portugal, France, and England may have been justified economically on the grounds that these monarchs had bankrolled the expeditions. In the Middle Ages, there were no private banking systems in Europe that had the ability to finance expeditions and there were no feasible alternatives to the kings having the necessary gold for the expeditions and, therefore, making all the rules.

In our initial story about the chemist, the engineer, and the economist finding themselves shipwrecked on a desert island, we need to ask ourselves on what basis should the economist appoint himself the authority on divvying up the foods extracted from the cans by the chemist, the engineer or both of them? The answer is there is none. The economist did not contribute any of his labor or capital to the endeavor. The chemist and the engineer have the natural right to keep the fruits of their own labors. Any food of theirs which they choose to give to the economist is the result of either charity or fair trade in return for the economist performing services for them, such as regaling them with his knowledge of microeconomics and macroeconomics (preferably Milton Friedman, Friedrich Hayek, Henry Hazlitt, and Ludwig von Mises). However, let us exchange the bespectacled economist for a brawny and muscular physical specimen of manhood, and his ultimate authority is derived from his perceived ability and actual use of violent force to rule the others and to seize for himself the fruits of their labors. The so-called “Divine Right of Kings” is, at its root, premised on the naked use of violent force by the original king or chieftain and the subsequent use of force by successive generations of his descendants. As many monarchies faded over time and were replaced by the governments of various representative democracies and dictatorships, their underlying authority ever remains the power of the sword regardless of any benign rationalizations that may be supplied by academicians and public relations spokespeople. The quantum of the taxation and regulation that governments will extract will always be the maximum long-run capacity of the victim to pay and obey, a proposition not too dissimilar from the lifelong symbiotic arrangement between an enlightened parasite and its host organism whereby the former’s appetite for sustenance wisely stops only a few drops short of killing the latter. The same will be true of any governmental efforts to tax and regulate Planetary Resources, Inc. and any similar asteroid-mining companies.

In concluding his article, Mr. Taylor made one of the more peculiar point that an economist can make. “Access to vast amounts of resources at minimal cost could benefit every single person on Earth. But if the drive to mine space is driven by greed then we could (will?) find ourselves in a position where a few people, for mere profit, control and severely limit access to the very assets that could set the human race free. Wars have been fought for less.” First, the notion of “vast amounts of resources at minimal cost” is nothing but a pipe dream. Developing and deploying the necessary technologies to venture into space will require vast amounts of resources by space entrepreneurs. “Minimal cost” is a fiction for there ain’t no such thing as a free lunch — even in space. Second, by virtue of being human beings, people’s drive to achieve and succeed, whether on Earth or in space, cannot possibly be driven by anything other than, shall we say, self-interest. If the human race is to be set free, free trade between parties who both benefit from the transaction is the only way to go.

In his seminal 1776 book The Wealth of Nations, the great economist Adam Smith demonstrated eloquently that, in a free economic system without central planning or coercion, each individual is “led by an invisible hand” and, paradoxically, by “pursuing his own interest he frequently promotes that of the society more effectually than when he really intends to promote it”. Professor Smith famously observed that “I have never known much good done by those who affected to trade for the public good” and added “It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer or the baker, that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest. We address ourselves, not to their humanity but to their self-love, and never talk to them of our own necessities but of their advantages.” Rather than offer empty platitudes and aspirational notions about how human beings ought to behave in a perfect world, Adam Smith demonstrated how, in a realistic world, self-interested individual behavior ultimately benefits all.

The prize for the most inane writings about Planetary Resources, Inc. mining near-Earth asteroids, however, must be awarded to one Randall Amster, who boasts a doctorate degree as well as a law degree and teaches Peace Studies and is Chair of the Master’s Program in Humanities at Prescott College in Prescott, Arizona. Mr. Amster opined in his April 26, 2012 article “Occupy Asteroids” in the Huffington Post (http://www.huffingtonpost.com/randall-amster/occupy-asteroids_b_1454469.html) that:

“the perversity of the asteroid-mining plan [is that] it merely continues the same paradigm of extraction and profiteering that has led us to the precipice in the first place. By virtue of their preexisting wealth, certain actors will be able to parlay that into laying claim to space resources that should be the property of no one, or perhaps everyone. This is merely an updated version of the doctrine of “prior appropriation,” which plies the misbegotten logic of “first in time, first in right” to privatize and control resources (like water and minerals) at the expense of common holdings, indigenous peoples, and environmental sustainability all at once.

“With all due respect to the folks at Planetary Resources, Inc., they can kiss our asteroids! They don’t own these rocks, or the moon, or any of the other heavenly bodies that occupy the skies above. It’s bad enough that their modus operandi has essentially turned the Earth itself into a globally privatized system (at least as far as profits go; losses are still sought to be collectively placed on all the rest of us to bear). Now they want to file title deeds and mining claims to the heavens, and by promising us cheaper toys in the process we’re not supposed to notice or care. Is that how it works?

“These issues were recently discussed in one of my college courses. I asked the students what could be done differently to make this a sustainable and just project rather than the one that’s on the drawing board right now. The responses were rational and visionary: the fruits of space exploration could be declared up front as the shared wealth of all peoples and nations; any profits or gains yielded could be directed toward the alleviation of poverty and inequality; any input of additional resources could include a moratorium on Earth-based extractive industries and a prohibition on wars presently fought for such resources; an expansion of the “closed system” in which we live could also include an equivalent expansion of creatively reusing waste products as is done on space stations.”

Unfortunately, it is quite possibly useless to argue with the idealist utopian vision that Mr. Amster advocates for us. One cannot rationally argue with a person who believes in the fantasy that animals in the wild live in peace and in perfect harmony like an animated Disney picture and averts his eyes to avoid seeing the violent deaths that carnivorous animals inflict upon their prey in reality as documented in National Geographic and Animal Planet programs. Likewise, Mr. Amster does not want to face the grim reality of living on this Earth and in this universe, where natural resources are finite and no amount of rationing and conservation can stave off ultimate depletion of resources and entropy. No amount of wishful thinking will transform the teeming mass of humanity into tribes of wise Native Americans or Africans with a zero carbon footprint like Pandora’s Na’vi who can magically sustain their entire people without wide-scale hunting and a backbreaking, dawn-to-dusk commitment to agriculture, presumably because realistically depicting such a neolithic society in Avatar would cause the romantic fantasy to dissipate, not to mention take away from Jake Sully and Neytiri’s screen time cavorting together.

History conclusively proves that every one of the superficially-sensible recommendations proposed by Mr. Amster and his students does not work in reality or is completely contrary to human nature. Space resources that are the property of everyone or no one? In 1967, 100 nations signed the Outer Space Treaty (formally the Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration of Outer Space Including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies) that declared extraterrestrial space to be res communis, the common property of humanity. It is no coincidence that, since the Apollo 17 mission of December of 1972, nearly 40 years ago, no human beings have set foot on the moon, which was completely predictable to students of history. The ancient Greeks knew that common property does not work and falls into neglect. Thucydides aptly observed 2,400 years ago in his book History of the Peloponnesian War that people “devote a very small fraction of time to the consideration of any public object, most of it to the prosecution of their own objects. Meanwhile each fancies that no harm will come to his neglect, that it is the business of somebody else to look after this or that for him; and so, by the same notion being entertained by all separately, the common cause imperceptibly decays.” Similarly, Aristotle wrote 2,300 years ago in his book Politics “That all persons call the same thing mine in the sense in which each does so may be a fine thing, but it is impracticable; or if the words are taken in the other sense, such a unity in no way conduces to harmony. And there is another objection to the proposal. For that which is common to the greatest number has the least care bestowed upon it. Every one thinks chiefly of his own, hardly at all of the common interest; and only when he is himself concerned as an individual. For besides other considerations, everybody is more inclined to neglect the duty which he expects another to fulfill; as in families many attendants are often less useful than a few.”

These incisive observations of human nature, made thousands of years ago by and about pre-industrial human beings, are ten-fold more true today. Notwithstanding advances in technology, human nature remains ever the same. Rational human beings, in any appreciable numbers, will not squander their limited time and scarce resources on the common property when they do not personally receive rewards reasonably commensurate with their investments, and, especially, when lazy freeloaders are allowed to share in the gains. Unless threatened with force and coercion, rational companies and people will never consent to invest their blood, sweat, tears, money, labor, and time in any endeavor that they know will be expropriated by others. Planetary Resources, Inc. and companies like it will not volunteer themselves to be the main course in the cannibals’ feast proposed by Mr. Amster and his students, regardless of the lofty ideological labels proposed by them, e.g., “environmentalism”, “shared wealth of all peoples and nations”, “common holdings”, “collective wealth”,”dictatorship of the proletariat”, or whatever.

The balance of Mr. Amster’s article rails against the project as attempting to continue to support same rapacious extraction of resources and wasteful consumerism that has caused the environmental catastrophe of today. He likens the space mining plan to “buying a new house to avoid cleaning up the old one” and asks, if the resources exist to mine asteroids, why should they not be used to “stop genocide, cure diseases, and promote free education and health care”. Mr. Amster is like a small child who only understands his own need for sustenance and resources, yet does not understand that his parents’ resources are not infinite or what labor, decisions, trades, and sacrifices must be made by his parents to obtain the resources that he timorously demands.

Going back to our earlier desert island story, the supply of canned foods on the desert island is finite. While it makes sense to consume the foods prudently and to avoid waste, the food will eventually run out and the three shipwrecked survivors will eventually starve to death. Unless more food is obtained from outside the closed desert island system, rationing and conservation will only delay, but will not avert the inevitable. If the shipwrecked survivors are fortunate to have a small life boat at their disposal, it makes sense for them to provision the life boat and send out one of the survivors to explore any larger land masses that may be within several days’ reach. Seeking new food sources is the only sensible, long-term possibility. This is true even if, during the first week of being shipwrecked on the island, the survivors failed to shepherd their resources prudently and acted wastefully. However, it logically follows that the three survivors must provision and send out the small life boat without delay before their resources dwindle to nothingness and the possibility of escaping slow starvation is extinguished forever. In contrast, if Mr. Amster were substituted for the economist in the story, he would berate the other survivors for their earlier wasteful actions and inveigh against sending out the boat, arguing that the life boat’s provisions should be owned in common equally by everyone without discrimination on the basis of race, national origin, ethnicity, religion, creed, disability, age, gender, physical beauty, sexual orientation or whatever.

In 1798, Thomas Robert Malthus presciently observed in his Essay on the Principle of Population that “The power of population is indefinitely greater than the power in the earth to produce subsistence for man”. He continued, “Must it not then be acknowledged by an attentive examiner of the histories of mankind, that in every age and in every State in which man has existed, or does now exist that the increase of population is necessarily limited by the means of subsistence, that population does invariably increase when the means of subsistence increase, and, that the superior power of population is repressed, and the actual population kept equal to the means of subsistence, by misery and vice.” Even two centuries ago, Malthus observed that human population increases to the limits of the food and the resources required to support it. With the world’s population at approximately eight billion people, environmentalism, conservation, and rationing can only go so far to somewhat slow down the rate at which non-renewable natural resources are depleted to nothingness.

If humanity does not send out the life boat while it still can in order to search for new resources, but, instead, devotes all of its available resources to “cleaning up its existing house” and to “stop genocide, cure diseases, and promote free education and health care”, as Mr. Amster advocates, the window of opportunity will close forever. The opposite of what Mr. Amster wants will happen. As food and resources dwindle, there will be more wars and more genocide because countries and people will fight even more ferociously over every remaining morsel of food and every scintilla of resources. Pestilence, war, famine, and death will reduce Earth’s human population to the limits of the food and resources required to support it. The utopia that Mr. Amster and his students fantasize about will not come to pass. Instead, our world will look more like the apocalyptic novel The Road by Cormac McCarthy and the 2009 motion picture bearing that name. This road to ruin must be avoided.